Designing a Ring Cycle for the 21st century

Director and production designer Chen Shi-Zheng is reimagining the great myth for a new age.

Wagner’s 15-hour, four-opera saga was first unveiled to the world in the second half of the 19th century, complete with its mythical world of dragons, dwarfs, giants, valkyries and gods. These characters immediately conjure up certain images we’re all familiar with — from art, literature, film and TV. But that’s not the imagery you’ll see on stage in director and production designer Chen Shi-Zheng’s new digital vision of the Ring Cycle for Opera Australia.

“I want to reimagine the myth as it is,” Chen says, “What you’ll see has very little reference to European, Western history, which is what most Rings have done. We are in Australia; we are in the Pacific Ring.”

Working with costume designer Anita Yavich and digital content designer Leigh Sachwitz from flora&faunavisions, Chen's Ring Cycle is all about building new worlds.

Four operas = four seasons

As spring is associated with the start of new life, it’s only appropriate that Chen’s cycle begins with a staging of Das Rheingold inspired by the season. Moving through the cycle, each opera is set in a particular season, but in no recognisable era or place.

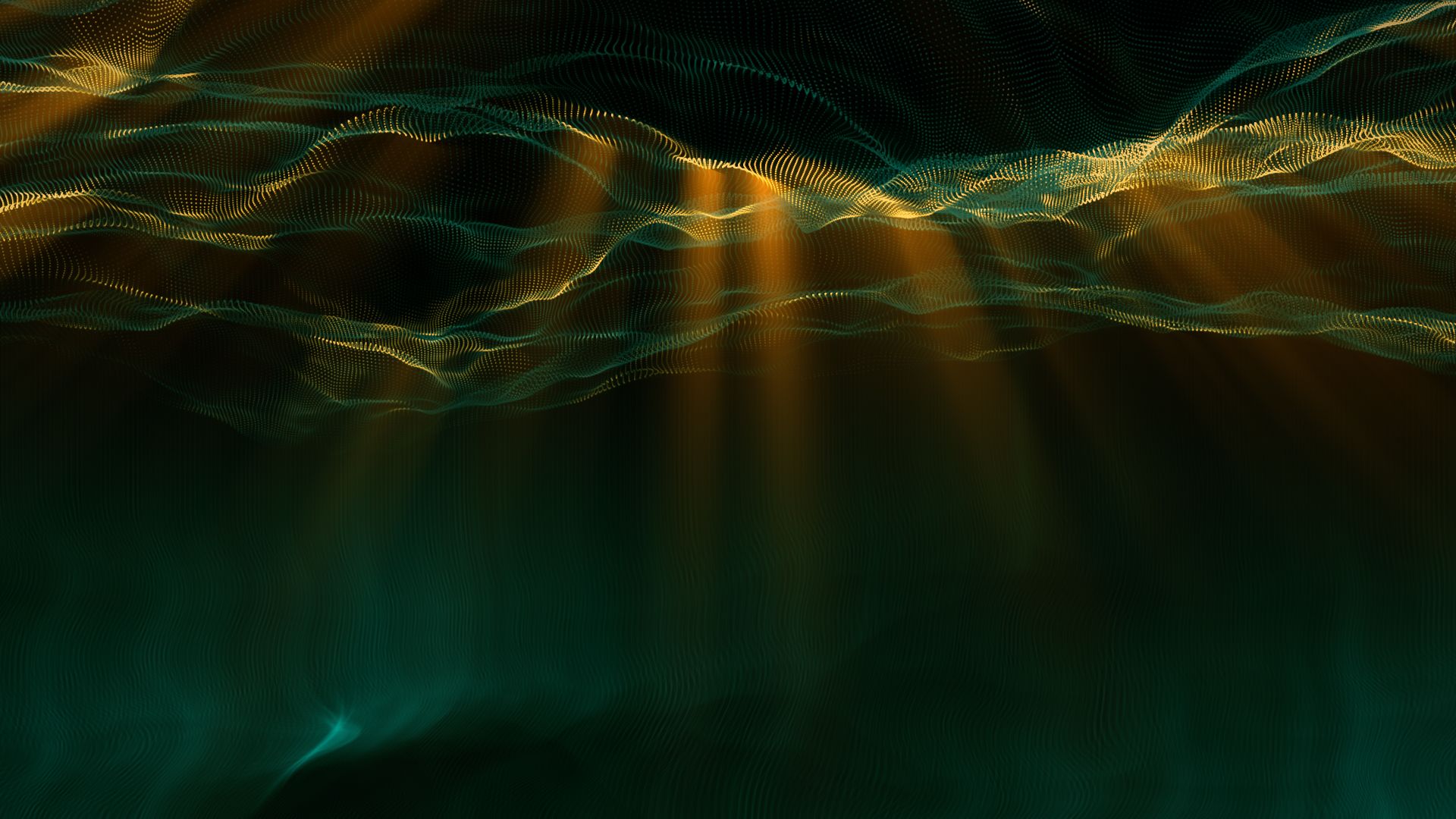

As the shortest opera in the cycle (at two and a half hours), Das Rheingold is an introduction to the characters and world, establishing the groundwork for the epic ahead. The opera opens on a world under the sea, with a huge piece of white coral, upon which the mystical Rhinemaidens frolic. Like most of the set pieces, it’s painted white , transforming in colour and texture with the help of lighting and video effects.

LED screens hark back to ancient theatre

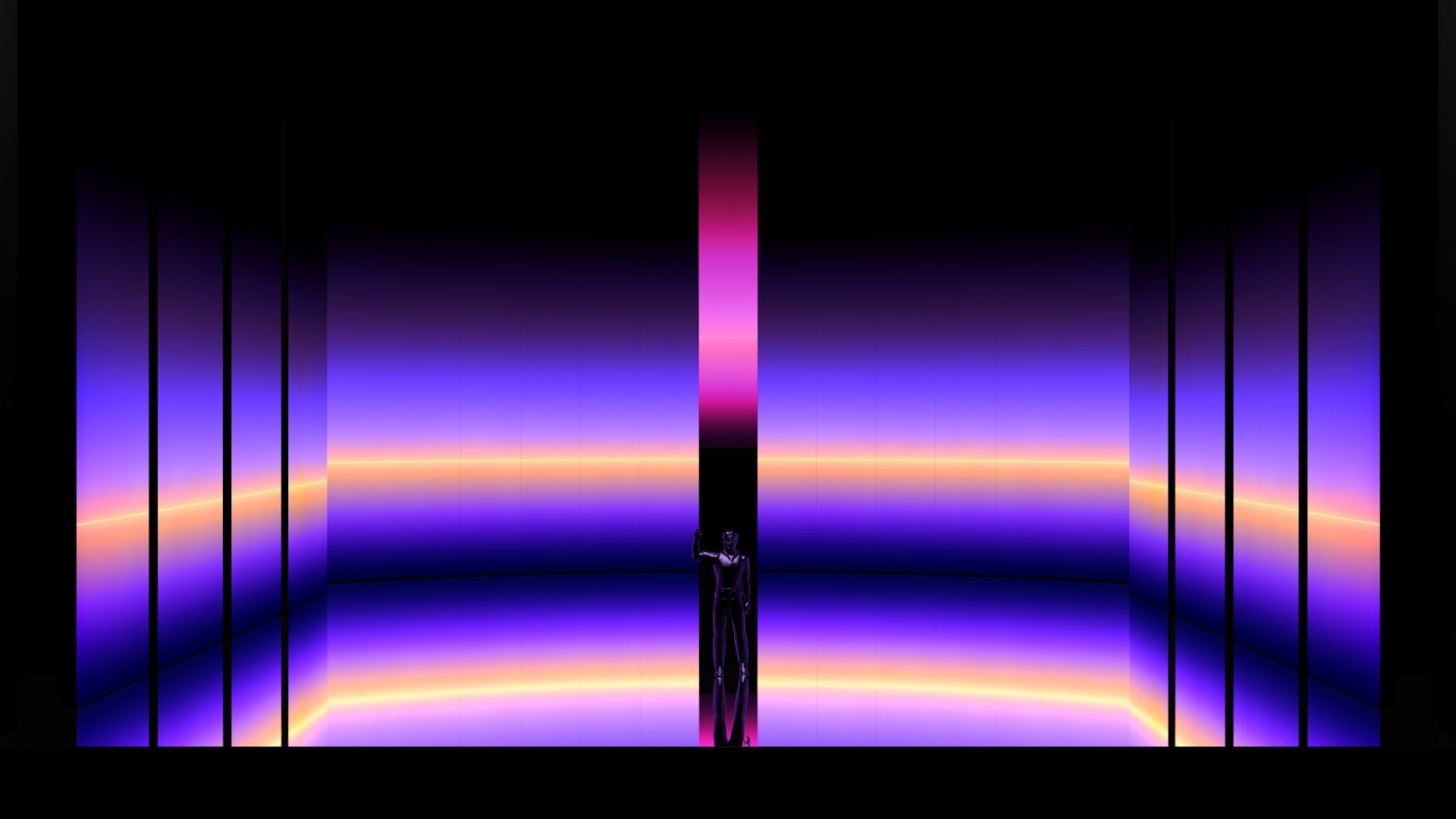

Digital technology doesn’t usually make you think of ancient Greek theatre, but the LED screen panels used in this production will suggest something timeless. Across the back of the stage, 15 panels are arranged in a giant curve. A further eight panels are along the sides of the stage and are able to move about the space.

“If you put all the panels on the side, it’s like a horseshoe. A bit like a Greek amphitheatre; the whole space is open,” Chen says.

The gods go intergalactic

The collaboration between designers and other creatives is essential to making any opera, but the connection between costumes and digital projections is integral to Chen’s production. The gods will appear in futuristic white trench coats which interact specifically with the set. This is key to the futuristic, space-age setting Chen has imagined for the world of the gods.

“The digital content is animated based on each god’s appearance, based on each god’s costume,” Chen says.

Nature at the centre

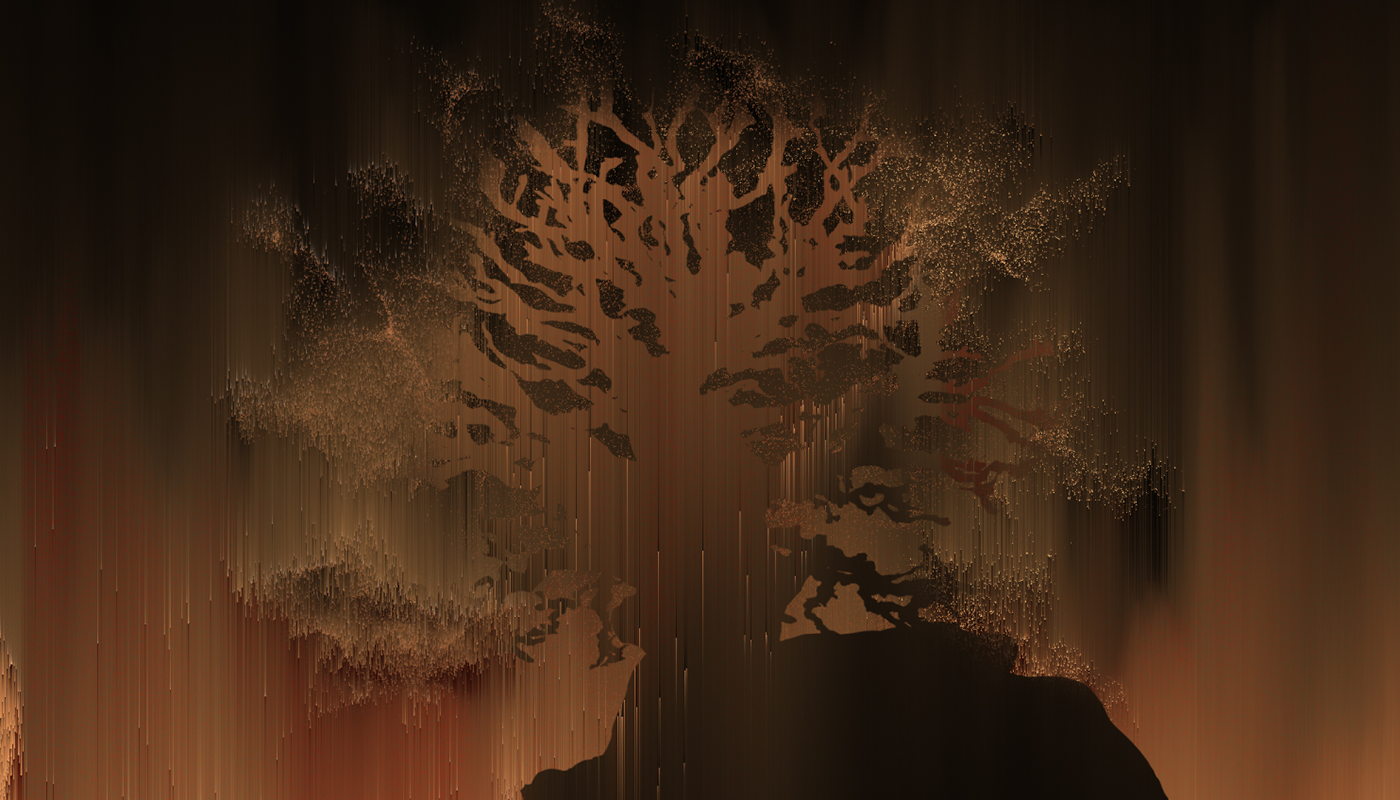

The natural world comes smashing together with cutting-edge technology in Chen’s vision. Think flowers, snow, rain, forests of trees, minerals from the earth, stone and fire. The “five elements” from Chinese philosophy — wood, fire, earth, metal and water — are a major inspiration.

One of the main set pieces in Die Walküre, the second opera in the cycle, is a seven-metre tall white tree, reaching up from the stage. It was modelled on a bonsai tree, which was 3D-scanned and then reproduced on a much larger scale.

Slaying the dragon

A pivotal scene in Siegfried, the third opera of the cycle, always presents a particular staging challenge: when the titular hero battles with a dragon. Directors have come up with different ways of bringing this moment to the stage, but Chen is using our digital screens to create something new. The audience will only ever see flashes of dragon, but never the full creature.

“It will be a digital dragon in panels,” Chen says. “To me it is almost like when you watch a video game slaying a dragon. When you do something, you go to the next level. In that sense, it’s kind of a game, you go through it until the dragon falls down.”

A frosty finish

As the final opera in the cycle, Götterdämmerung is set in winter, in a kind of apocalyptic ice world. Those familiar with the opera will know that fire plays a pivotal role, so the contrast between this world of icy cold and the scorching, redemptive heat of fire will make an enormous impression.

As the opera draws to a close, the ground is laid for new life to begin again as we enter spring and the cycle begins again.

Photographs: Rhiannon Hopley.

Digital set renders: Leigh Sachwitz / flora&faunavisions