From Othello to Otello

Huw Griffiths (Associate Professor of English, University of Sydney) explains how one of Shakespeare’s greatest and most distinctive tragedies took unique operatic shape – almost three centuries after the play’s premiere.

From Othello to Otello

Huw Griffiths (Associate Professor of English, University of Sydney) explains how one of Shakespeare’s greatest and most distinctive tragedies took unique operatic shape – almost three centuries after the play’s premiere.

A difficult task

When Arrigo Boito, Verdi’s librettist, adapted Shakespeare’s play into a new opera during the 1880s, he was faced with a uniquely difficult task. Not only did he have to wrangle Shakespeare’s typically sprawling play into the more condensed form of an opera, he also needed to contend with the very mixed reputation that the play had picked up since its first performances in 1603.

Librettist Arrigo Boito and composer Giuseppe Verdi, who created Otello, the operatic adaptation of Othello (using the Italianised version of the name as its title.)

Librettist Arrigo Boito and composer Giuseppe Verdi, who created Otello, the operatic adaptation of Othello (using the Italianised version of the name as its title.)

Responses had ranged from offended condemnation to passionate celebration. Early reception of Othello focused on what many critics considered to be the immorality of its plot. One particularly vehement reaction was that of the writer, Thomas Rymer, who, in 1693, criticised the play for being utterly implausible: “ … never was any Play fraught, like this of Othello, with improbabilities”. Chief amongst these improbabilities, for Rymer, was the love of Desdemona for Othello: “This Senator’s Daughter runs away … with a Blackamoor, is no sooner wedded to him, but the very night she Beds him, is importuning and teasing him for a young smock-faced Lieutenant, Cassio”. Critics in the late seventeenth and through the eighteenth century had a tendency to think that narratives were only plausible, and plays only well-written, if they also exhibited what they considered to be an acceptable morality. It is no surprise, then, that the racist attitudes that underlie Rymer’s supposed incredulity lead, for him, to a conclusion that we need not expect anything “either true, or fine, or noble” from Shakespeare’s characters.

The play underwent a major reassessment in the early nineteenth century under the auspices of Romanticism, the artistic movement that swept away what it saw as the false rationality of the preceding years. For writers like William Hazlitt, Othello became a figure of impassioned heroism, pitiably caught in the traps laid out for him by Iago and by Venetian society. Hazlitt, in 1817, wrote that, “The nature of the Moor is noble, confiding, tender, and generous; but his blood is of the most inflammable kind; and being once roused by a sense of his wrongs, he is stopped by no considerations of remorse or pity till he has given a loose to all the dictates of his rage and his despair.”

By the nineteenth century, the violence of the play was no longer considered to lack moral structure but rather seen as the inevitable result of overwhelmingly human passions.

Changed histories

At the same time as this changing critical context, the world itself had changed. There is a telling detail in the opera that indicates the extent of historical difference between Shakespeare’s early seventeenth-century play and the 1880s. In Otello, Desdemona claims – during her duet with Othello at the end of Act 1 – that her husband told her, “of the pains you suffered as a slave in chains”. This detail of Othello’s former life is not included in the Shakespeare play.

An obvious historical narrative lies behind this addition. In the early seventeenth century, the European trade in African slaves was in its infancy. But, in the intervening years, the Atlantic slave trade had grown massively before coming to an end with the last boat of slaves arriving in the US in 1859. The murderous trade might have come to an end at the point that the opera was written, but European colonialism was still in full flight, and the full weight of that violent history lies behind the words that Boito gives to Desdemona at this point.

Otello at the Sydney Opera House (2014). Photo: Branco Gaica.

Operatic solutions

Shifting histories and mixed critical legacies presented Boito and Verdi with a number of challenges. However, as with all successful adaptations, the solutions that they come up with end up making a virtue out of necessity.

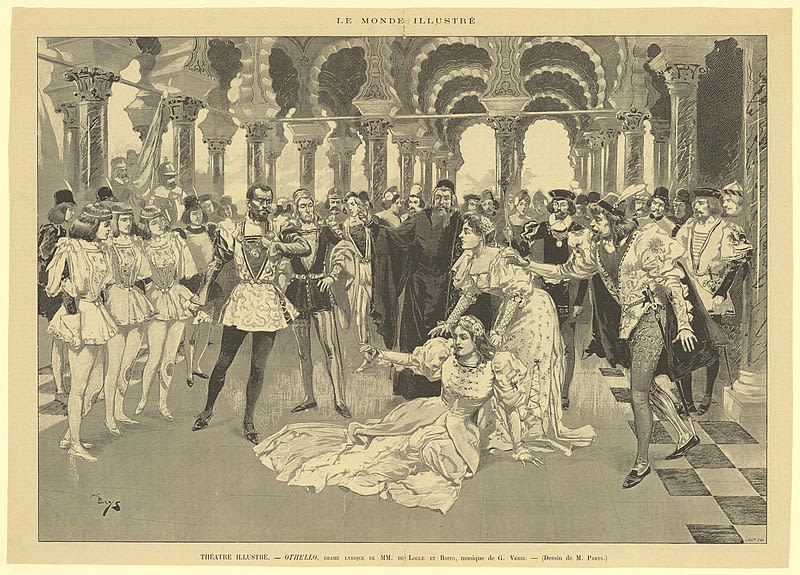

Press illustration of the 12 October 1894 Parisian premiere of Otello.

Press illustration of the 12 October 1894 Parisian premiere of Otello.

Curtailing what would be the excessive length of Shakespeare’s plot for an opera, they omit the first act entirely. A major effect of this is a more intense concentration on the relationship between Desdemona and Othello. Act 1 of the play centres on Othello’s public defence of their relationship against the racism manipulated by Iago and taken up by Desdemona’s father, Brabantio. Act 1 of the opera instead culminates in a duet in which the married couple declare their love for each other. The duet borrows some of the words from the Shakespearean Othello’s public declaration but it distributes them between the two lovers in a more intimate, mutual statement of shared love. The opera avoids some of the difficult questions that Shakespeare’s play asks about the social contexts within which their relationship might be understood by idealising the couple as both heroic and virtuous.

From this shift in narrative perspective also emerge two of Boito and Verdi’s most compelling innovations in their re-imagining of the characters of Iago and Desdemona.

From demonic credo to Ave Maria

Prior to writing the libretto for Otello, Boito had written his own opera, Mefistofele, a version of the Faust story. He takes some of the demonic energy of that piece into the character of Iago. A unique moment in the opera is Iago’s “Credo”, a statement of purpose that is entirely missing from Shakespeare’s Iago who, right until the end of the play, refuses to make explicit the reasons behind his actions.

Early in Act 2, having set his plan in motion, Iago is alone on stage and, in one of the most powerful moments of the opera, sings his aria, ‘Credo in un Dio crudel’ (“I believe in one cruel God”). It is a demonic, but brilliant, rewriting of a core statement of Christian belief, the Nicene creed (“We believe in one God”). Iago doubly places himself outside of the community that he seeks to manipulate, first by pledging allegiance to a cruel, rather than to a true, God and then by going alone. His is a testimony of individual belief rather than the collective statement of the creed.

A counterpart to Iago’s misuse of religious language is Desdemona’s ‘Ave Maria’ later in the opera. Just as she does in the Shakespeare play, Verdi and Boito’s Desdemona sings a version of the ‘Willow Song’ as she prepares for bed. The “willow song”, in Shakespeare’s England, was a song that spoke of a young woman’s grief at the loss of her love. In the opera, however, this secular ballad merges into, ‘Ave Maria, piena di grazia’ (Hail Mary, full of grace). Like Iago, she turns a fundamental statement of belief from the Catholic church to her own purposes. However, those purposes are far from demonic as she prays for, “one who bows the head under outrage and wicked destiny”.

Shakespeare takes a much more equivocal approach to his characters than Verdi and Boito: his Iago remains ambiguously motiveless and Desdemona is never presented in the starkly virtuous terms afforded her by the opera. The anxious contexts of Shakespeare’s post-Reformation England tended to produce artistic works that hesitated to make definitive statements. Boito and Verdi’s opera is, on the other hand, bold in its outline of character and decidedly Catholic in its forthright adoption of religious language.

In navigating the problems, both structural and reputational, that they inherited from the life of this play over the preceding 280 years, Verdi and Boito present a solution that has a particular life of its own. If some of the subtle ambivalences of Shakespeare’s rather prickly play are lost, then what is gained is something much bolder, more dramatic in its contrasts and much more intense in its focus on the passions of its protagonists.

Otello at the Sydney Opera House (2008). Photo: Branco Gaica.