The Wagner Effect

Our beginner’s guide to the German composer who revolutionised opera.

Richard Wagner has hordes of diehard fans who will enthusiastically tell you about their obsession, happily travel the globe for a fix of his music, and spend thousands on recordings of his work.

But why does he hold such a special place in the heart of so many opera lovers? And how did he revolutionise the art form?

Who was Richard Wagner?

Wagner was born in 1813 in the German city of Leipzig, and was the ninth child of his parents; his father was a police clerk and his mother the daughter of a baker.

Just six months after Wagner’s birth, his father died and his mother started a relationship with an actor and playwright, who became Wagner’s stepfather. This man helped inspire his love for the arts.

Wagner studied both music and drama – and at one stage had ambitions as a playwright – but early on in his life became interested in how drama and music can be fused together as opera.

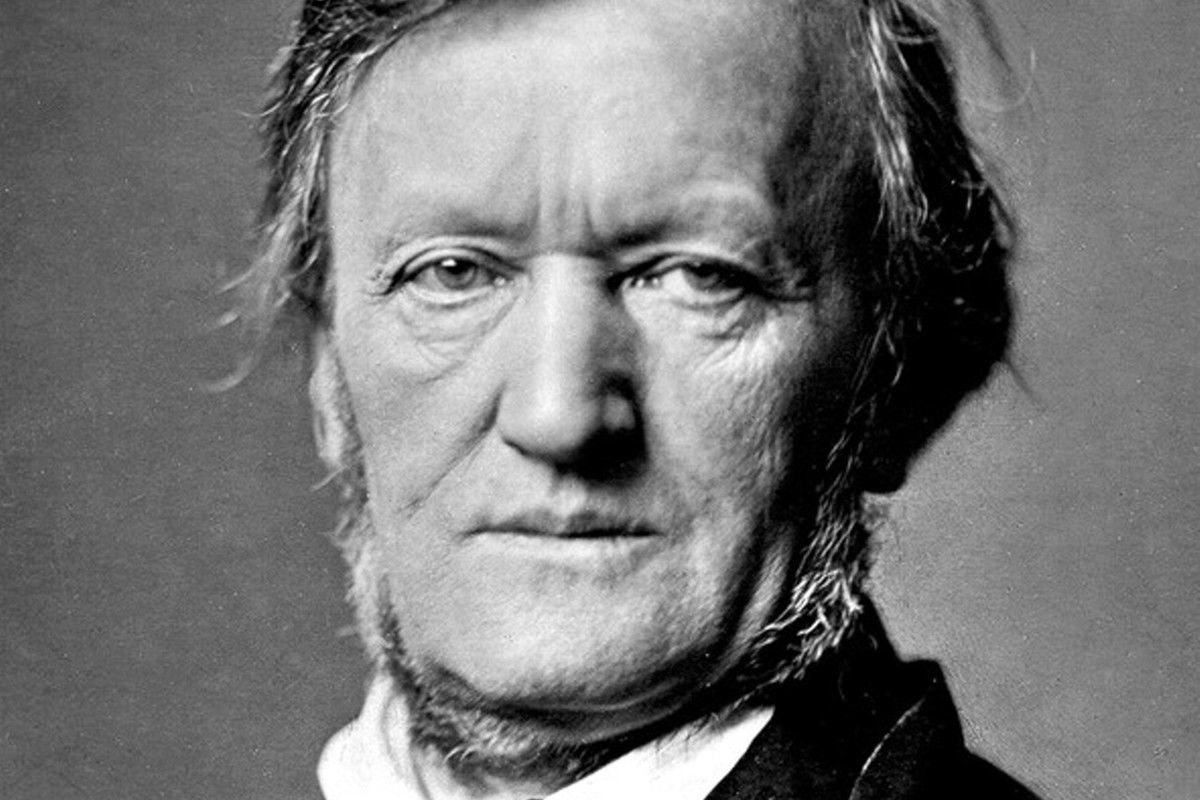

A portrait of Richard Wagner

A portrait of Richard Wagner

His first few operatic works didn’t make a huge splash, but it was in The Flying Dutchman, composed in Wagner’s late twenties, that his innovative musical voice started to really cut through. His true masterpiece was the Ring Cycle, a sprawling 16-hour fantasy, performed over four nights of opera.

He lived across Europe for much of his life, but spent several of his later years in the German city of Bayreuth, where he started an opera festival. The festival continues to this day, performing his works and drawing Wagner fans from all over the world. You have to apply for tickets, and the festival is so popular it can take up to ten years before you finally get selected!

Wagner revolutionised opera in a number of ways, breaking the rules and ambitiously setting the art form on a new course.

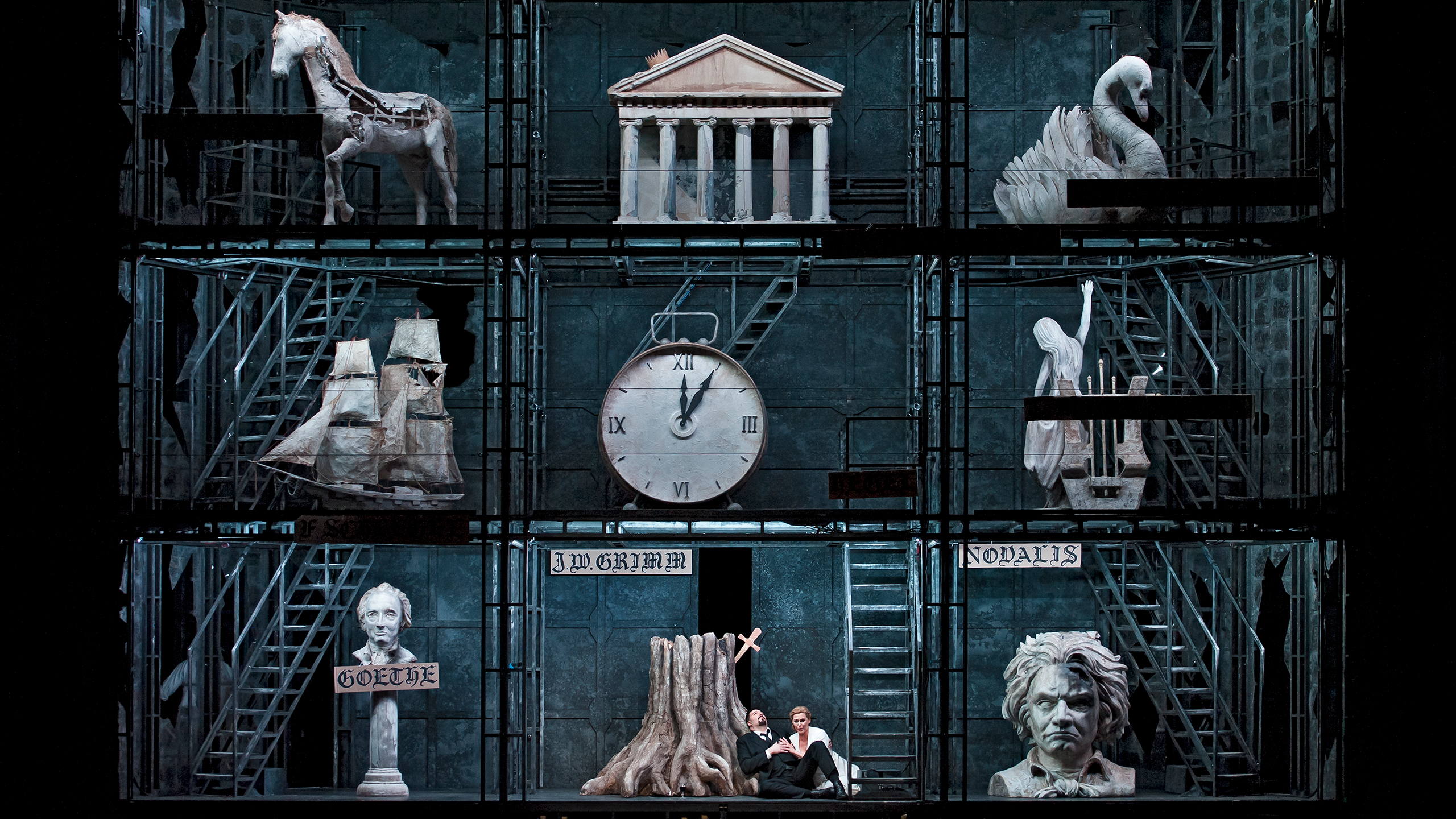

Lohengrin at La Monnaie (2018). Photo: Baus.

Champion of the leitmotif

Wagner popularised the ‘leitmotif’, a musical concept in which a short musical phrase represents a particular person or idea in a dramatic work. He didn’t invent the idea, but his Ring Cycle showed how effectively leitmotifs could be used, with some recurring throughout multiple operas.

Leitmotifs are now used in all sorts of works: major musicals like Hamilton and The Phantom of the Opera, and even in movies. You probably know the leitmotifs associated with Darth Vader in Star Wars or the shark in Jaws. You’ve got Wagner to thank for that!

Das Rheingold from the Ring Cycle at Arts Centre Melbourne (2016). Photo: Jeff Busby.

What music might I already know?

There are two pieces you can probably hum. The first is the Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin, better known as ‘Here comes the bride’. (No, Wagner’s does not mention anything about a banana peel or a broken backside.)

The second is the sort of big, bombastic orchestral music most people think of when you say Wagner: the Ride of the Valkyries from the Ring Cycle’s second chapter, Die Walküre.

Lohengrin at La Monnaie (2018). Photo: Baus.

Gesamtkunstwerk

The Germans truly do have a word for everything, including gesamtkunstwerk, which means a “total work of art”. Wagner was a huge proponent of this idea.

He was critical of the way the various arts had fractured and wanted to create works that unified different art forms and forms of expression – music, text, movement, design, all working together to achieve the same goal. According to Wagner, nobody had managed to do so since the Ancient Greeks.

He thought that opera had become a vehicle for showy spectacle and vocal “numbers”, and sought to write operas that were fully integrated expressions of cultural truths. Radically, many of his operas don’t really have defined “songs”, but are instead composed-through works of drama.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at Arts Centre Melbourne (2018). Photo: Jeff Busby.

The Ring Cycle

Wagner’s crowning achievement is undoubtedly the Ring Cycle (its formal title is Der Ring des Nibelungen). The Ring Cycle is a collection of four operas, which together tell an epic, fantasy story of gods, warriors, dragons, giants and other magical creatures drawn from Norse mythology.

A full “cycle” takes four nights to perform, and is an absolutely epic undertaking for any opera company. In fact, it’s known as the Everest of opera. It requires an enormous cast and singers with incredible stamina – the longest opera of the four is six and a half hours, including intermission.

Opera Australia only performed our first full Ring Cycle in 2013 at Arts Centre Melbourne. That production was revived in 2016, and we’re due to perform a brand new production in Brisbane in late 2023.

Die Walküre from the Ring Cycle at Arts Centre Melbourne (2016). Photo: Jeff Busby.

The Wagner controversies

While Wagner’s works are considered among humanity’s greatest artistic achievements, he has a complex legacy. Like many (if not most) Germans of his day, Wagner expressed anti-Semitic views, including in his now infamous essay Jewishness in Music. Musicologists and academics have also long debated whether there’s antisemitism inherent in his operas themselves.

For these reasons, Wagner’s name often comes up when people debate whether or not you can separate an artwork from the artist who created it, and still enjoy the work.

But Wagner’s legacy is further complicated by his association with Nazism. Although Wagner had died long before Nazism’s rise, his music was appropriated by the party and frequently played at rallies. Adolf Hitler was fanatical in his devotion to Wagner’s compositions, and even had several of Wagner’s original scores with him in his Berlin bunker at the end of World War II.

For this reason, Wagner’s operas have never been staged in Israel, and there is much debate there over whether or not his music should be played.

Die Walküre from the Ring Cycle at Arts Centre Melbourne (2016). Photo: Jeff Busby.

A pre-cursor to Modernism

It’s difficult to overstate the impact Wagner had on the world of opera, music and drama. In fact, some commentators believe Wagner was a pre-cursor to the Modernism movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reflecting the new industrial world.

In the music world, Modernism saw some great experiments in dissonance (putting clashing notes together) and atonality (melodies and harmonies that lack a “centre” or a tonal anchor).

Wagner’s “Tristan chord”, which he used in the prelude for his opera Tristan und Isolde, is considered by many as the start of modernism in music. The chord feels unresolved in its context, and was unexpected and challenging to listeners at the time.

Lohengrin at La Monnaie (2018). Photo: Baus.